Rising star Billy Gerard Frank is known as a multidisciplinary artist—a remarkably talented painter, designer, and filmmaker who happens to be self-educated. But whether he’s holding a paintbrush, a pencil, or a camera, it’s the artwork’s message—not the medium itself, that most motivates him.

That message is often deeply personal. Billy’s upbringing on a small island off Grenada in the West Indies informs, influences, and inspires his art, which often explores themes of race, migration, global politics, sexuality, and colonialism.

At heart a storyteller and an educator, he’s always eager to engage his viewers, stimulate conversation, perhaps inspire self-reflection, and ideally, bring about healing. With a series of recent paintings, Billy is doing just that.

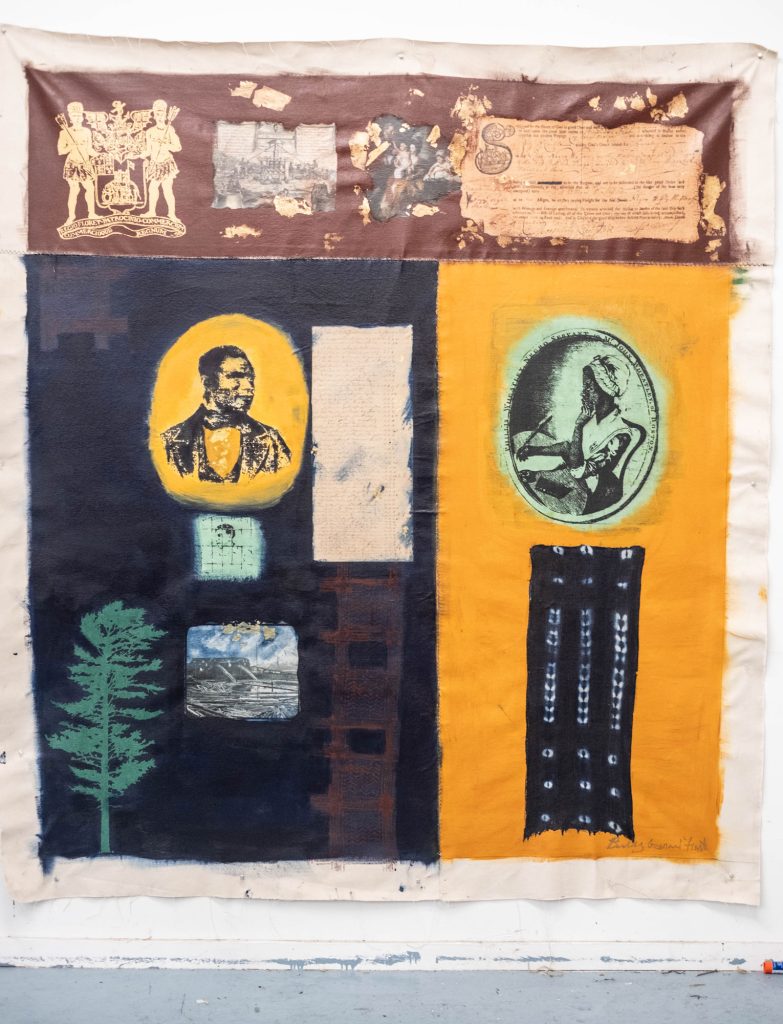

Produced in delightful collaboration with illustrious Portland printmaker David Wolfe, Indigo Entanglements exquisitely examines the roots of slavery with multiple silkscreen images of individuals, slave ships, maps, text, and other elements to illustrate a story that isn’t always found in history books.

“Indigo” refers to the trade of indigo pigment in the Caribbean and the deep, rich color’s association with royalty, while “Entanglements” concerns the complicated history of slavery, involving more people and places than typically recorded. “It’s such an important time to be telling this story,” says Billy via telephone from his studio in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood. He explains that since the Back Lives Matter movement, there’s been an opennessto talking more about slavery. “This art is kind of a conversation piece, and people seem moved by it. These works encourage an honest conversation about it from a historical perspective.”

One art-collecting couple was so moved, especially by Indigo Entanglements No. 5, which speaks specifically to Maine’s role in the slave trade—timber sourcing and boat building, in particular—that they purchased and donated it anonymously to the Farnsworth Art Museum.

“We’re so excited about this gift,” says Jaime DeSimone, Chief Curator at the Farnsworth, which for 75 years has been celebrating Maine’s role in American art. “It tells a story that we struggle to tell. “We know Maine had a history with the Atlantic slave trade, she says. “But there aren’t a lot of archival materials to tell these stories, nor are there artists of color from that time who could give visibility to art of that time. They didn’t have a voice. Billy had mined many archival materials to understand complex narratives. Front and center in this work is a map, so we can all recognize where Maine is in that conversation.”

It’s not a relationship that is well-known and might come as a surprise to some. “We were building ships that were used to bring Africans in,” explains David Wolfe. “It wasn’t common for Maine to have slaves, but there was a financial connection that cannot be overlooked.” He recalls that during the intensive month last summer when he and Billy created the series (a partnership they both speak of glowingly), a parade of people stopped by to get a glimpse of theirwork, and many of them remarked “Oh, I didn’t realize that.”

Jaime says the Farnsworth intends to create a caring, respectful viewing space, where visitors can experience the work quietly or perhaps engage in dialogue about it during an event surrounding its unveiling.

Elizabeth Moss, owner of Elizabeth Moss Galleries in Falmouth and Portland, who made the connections between the artists, donor, and the museum, is thrilled that this important work has found a home in the Rockland museum’s collection. “This is the most important painting I’ve sold in 20 years,” she says, “because of its potential as a catalyst for conversation about race in our state’s history and the impact it will have on visitors at the Farnsworth.”