The mystique of Maine’s light-dappled forests and rolling sea has a long history of entrancing makers. For the most inspired of them, Maine is not just a coordinate but rather a calling.

The 12 Maine craftspeople profiled here reinforce the state’s underlying heritage and rhythms of nature that encourage a handmade lifestyle, resulting in beautiful practicality. From pottery to woodwork to textiles, jewelry, and more, the functional wares of these artisans pay homage to a cultural lineage abundant with fishers, foragers, and farmers while infusing a subtle modernization that is giving Maine’s endearing rough edges a little gleam.

These “axes” play as good as they look.

Marquetry makes these instruments a sought-after rarity.

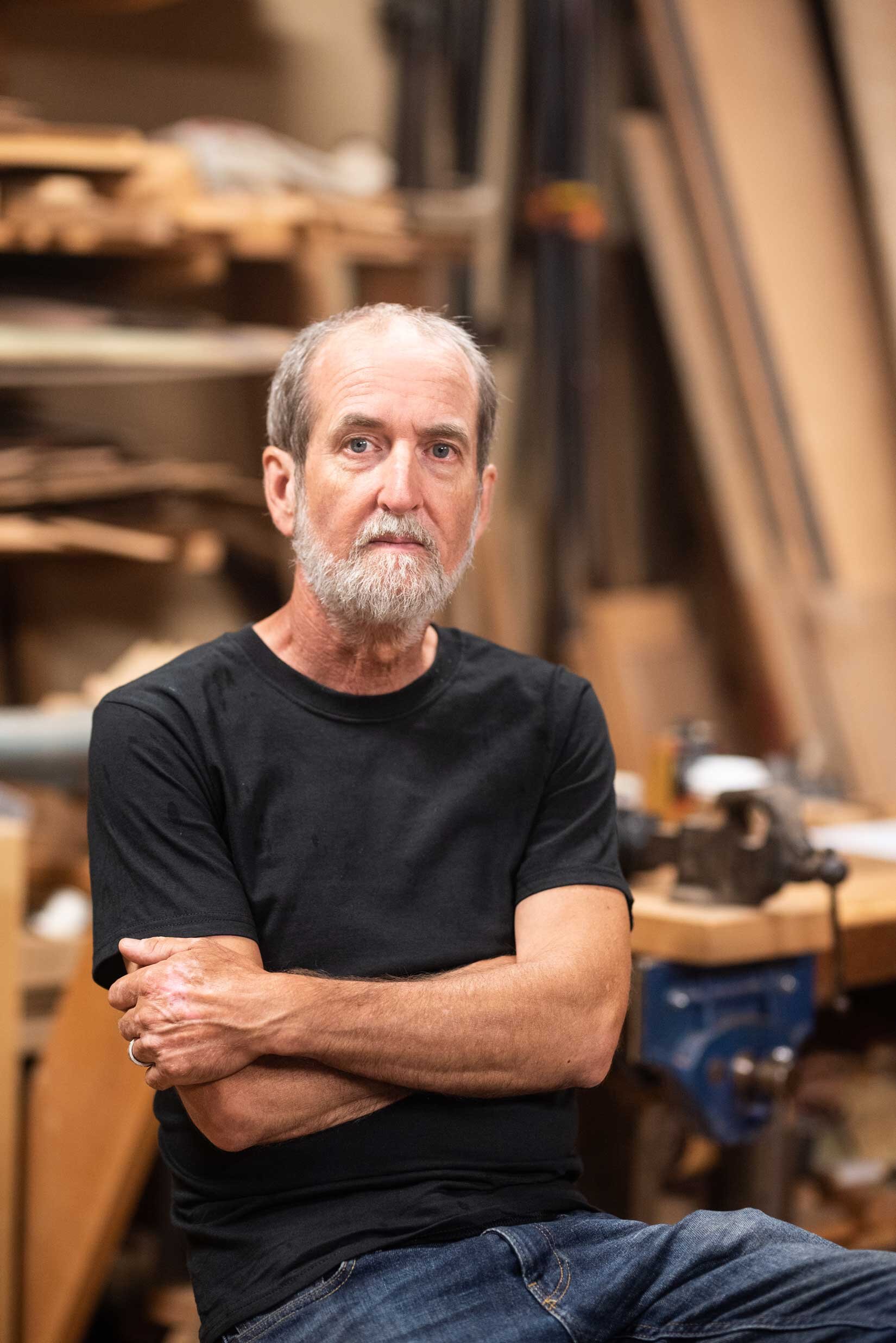

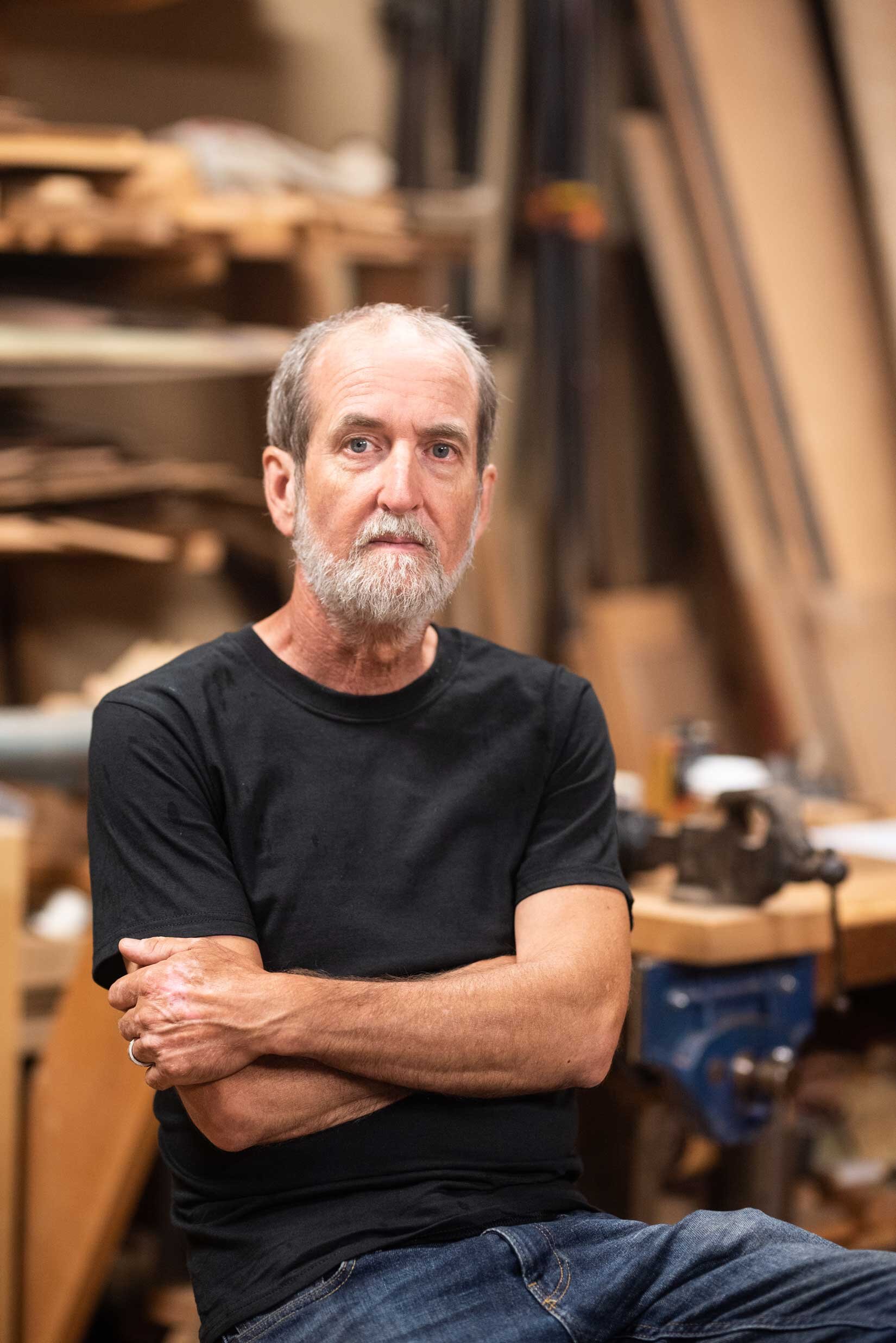

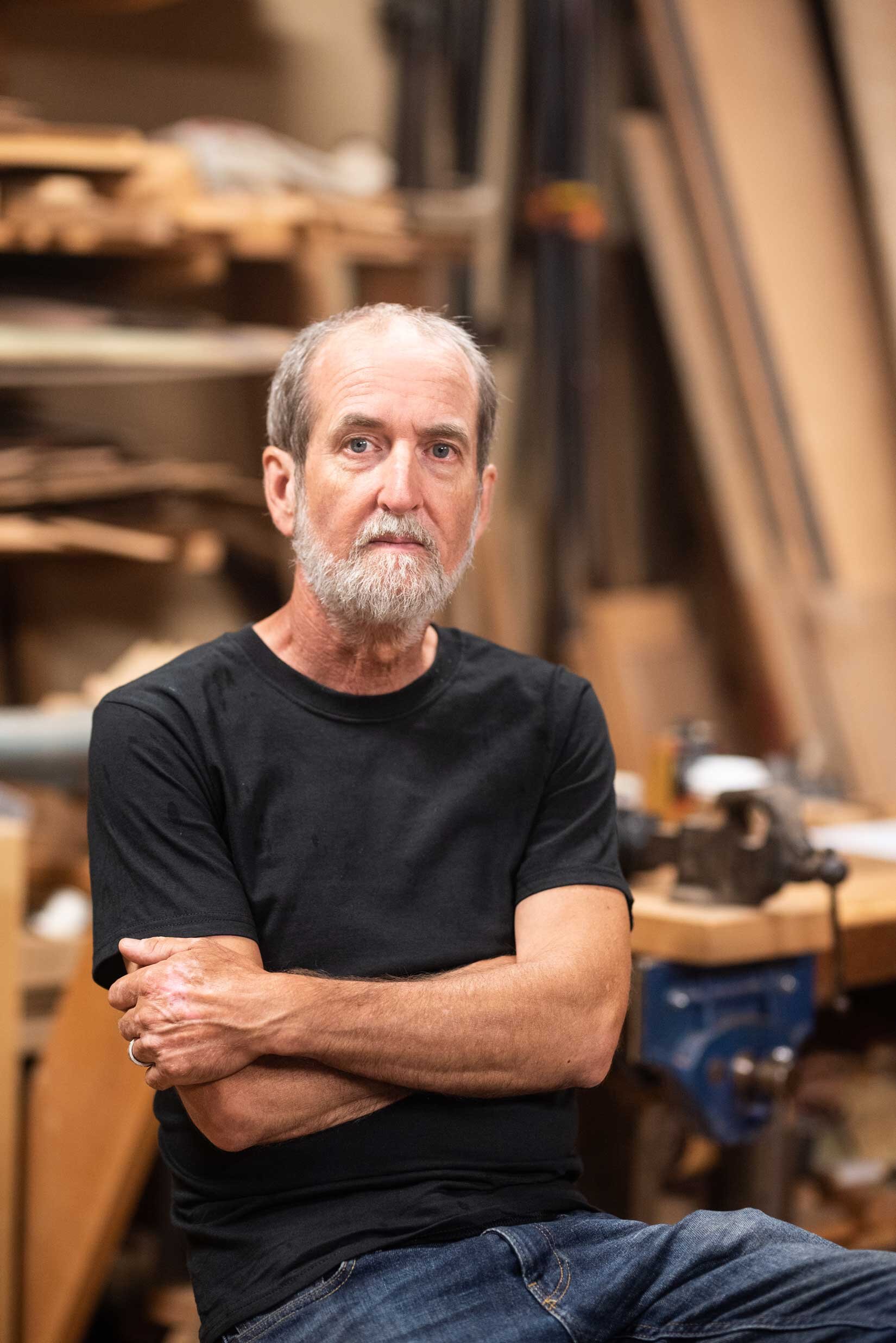

Guitar making was a natural segue for James Macdonald, who dreamed of rock stardom.

James Macdonald in his shop.

A Musical Marquetry Medley

James Macdonald explores and expresses the shared experiences of his generation through his thought-provoking marquetry pieces: artworks created by cutting and piecing together different types and colors of wood veneer, also featured on his custom-made guitars. Motifs found within his one-of-a-kind pieces include music and albums, books, nature, and food. One marquetry piece titled Reverence depicts a moody scene: a hand blooming from a corncob husk. A vibrant guitar titled Tribute to Clapton showcases inlaid imagery from two of the musician’s standout album covers. Yet these examples—mesmerizing as they are—hardly scratch the surface of James’s capabilities.

But to understand James’s work, you must first understand the artisan, who grew up set on becoming a rock star. With Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Beatles, and The Allman Brothers coursing through his generation, James learned and mastered the guitar while tinkering in his family’s modest basement wood shop. At 20 years old, he read The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking, and upon turning the last page he began a lifelong pursuit of—and subsequent career in—craftsmanship. “It’s a way of retracing my roots,” James says of his creative process, underscoring the desire for each finished product to hold the ordinary up to a spotlight, revealing the surprising beauty in every detailed layer.

“Weaving is both an art and a science,” says Hilary Crowell.

Unique color combinations and organic patterns are cultivated within these textiles.

Whether tea towel, mat, or coaster, The Cultivated Thread products are both fashionable and functional.

Hilary Crowell, proprietor of The Cultivated Thread.

Weaving Meaning from Field to Loom

Hilary Crowell, proprietor of The Cultivated Thread, weaves towels, napkins, coasters, shoulder and zipper bags, place mats, and more from her home studio in Bath. Her work is a beautiful statement piece but also a functional tool that, as she explains in regards to towels, “is always in hand, used to mop up a mess, dry dishes, or cover a rising loaf of bread.” Function, form, color, and—surprisingly—a lot of math inform her intricate and vibrant textile patterns. Although perhaps what inspires her most is, in true Downeast fashion, being surrounded by others who appreciate items that another human has put work into. “I feel so lucky to do this work, within this community,” says Hilary. “I am constantly filled with gratitude.”

Likening the act of creating her wares to cultivating a line of crops, Hilary credits her maker mentality to a Waldorf education. It was at school that she learned to knit (in the first grade) and later to weave (in the fourth grade), and where she developed a lifelong appreciation for items made by hand—even food. (Hilary is a maker in another sense as well, having farmed Maine’s rugged landscape for 13 years.) As she speaks, the intricacies that thread farming and weaving together for her become clear. “I like to put things in order, and that is important both on the loom and in the fields,” she says. “I’m constantly asking myself what it means to cultivate.”

Pamela prefers working with warmer metals, like bronze and gold.

Inspired by folklore, symbolism, and the forest, each Honey Tribe piece holds a bit of soulfulness characteristic of its maker.

Pamela Desantis, proprietor of Honey Tribe.

Pamela Desantis models a handmade pendant. Photos by Jen Dean Photography

“I want my work to feel as though it were unearthed from a tomb,” Pamela Desantis, proprietor of Honey Tribe, says. Her custom jewelry is imbued with mysticism, drawn from the forest, or, in some cases, customer stories. “I think of my work as talismans, or amulets,” Pamela says, referring to the ways she uses folklore and symbolism behind certain stones to empower the wearer. Her preferred medium of warm metals—such as bronze and gold—and irregular and imperfect stones makes it easy to mistake a brand-new Honey Tribe piece for a priceless family heirloom. The difference may be the individuality she layers in. “My hand is undeniably imprinted in each of my creations,” Pamela says. Each ring, necklace, pendant, cufflink, and bracelet wears a part of her creativity proudly, a factor that distinguishes her pieces from the more common fine jewelry variations.

Pamela’s family lineage in the arts prompted her to study sculpture and printmaking before finally settling on jewelry making. From her well-loved 1790s-era cape-turned-studio in Kennebunk, Pamela sets the creative mood by dimming the lights, cranking the music, and letting sparks fly. Much hammering, soldering, and one-of-a-kind energy flow inform a particular piece. Whether a custom request, creative exploration, or popular reproduction, expect a Honey Tribe product to be crafted with a decade of experience in its wake, and to carry a certain irreplicable timelessness that clings to these hand-forged adornments.

Playful Process Shapes Sophisticated Metalwares

Cufflinks, pendants, bracelets, and rings are just a few of the items Laura joyously creates.

Laura Friedman’s textured jewelry is simultaneously modern and rustic.

An eccentric pendant accentuates the metal’s organicism.

Laura Friedman, proprietor of lsf | design + fabrication.

During a rewarding career working with young children, Laura came to fully appreciate the importance of creative expression in development, prompting her to later enroll in an eight-week adult education class at Maine College of Art in metalsmithing. Equally intimidated and invigorated, Laura pushed on, pursuing one more class before setting up a studio in her Cumberland home, complete with a mini torch and an insatiable desire to play, explore, and express through her chosen medium of metal.

Each of her distinctive pieces takes between a few hours and a few weeks to create and begins with sheet metal and wire, evolving and growing from there. Of her creative process, Laura says, “My work with children has really restored my faith in how people learn intrinsically. It’s so important—even in adulthood—to play with materials and make mistakes. Everything has the potential to be something beautiful once the fear of failure and judgement is overcome, and the process is simply enjoyed.”

From Boats to Baths to Brilliance

The Batiste’s wooden bath (and sink) looking right at home. This Canadian dwelling was built by architect Charlie Lazor. Photo by Pete VonDeLinde.

Stephen and Miranda Batiste, proprietors of Bath in Wood of Maine.

As a boy growing up in London, Stephen took on the task of repairing wooden rowboats while attending school along the River Thames. It was years later—appropriately, while repairing a wooden boat with Miranda—that the seed for making wooden bathtubs was planted. When the couple found a home here in Maine on Swan’s Island, they eagerly pursued using the state’s abundant natural resources to make Bath in Wood of Maine a reality.

Influenced by the Japanese concept of sukiya, a term that Stephen translates as “refined simplicity,” the bathtubs created in the couple’s workshop have a natural, subtle elegance. Built exclusively with hardwoods, the tubs are fit together in a tongue-and-groove fashion and sealed with a finish that allows for regular bathtub use and care. Always striving for excellence, Stephen and Miranda craft their tubs by hand, each taking roughly 100 hours to complete. Ever humble, Stephen draws inspiration from his theatrical background for the tub designs, but is quick to add that the distinguishing characteristic of each tub is its durability.

Traditional Tactics Suit Cumberland Timber Hewer

Stephen Smith hews fallen trees into the rough beams shown using just his axe. Photos by Stephen Smith and Brian Threlkeld.

Live-edge serving boards are an organic adornment for any kitchen.

Beam finishes range from linseed oil to stain, poly, and more.

Stephen Smith, proprietor of Renaissance Timber.

And Stephen is no stranger to patience. Hewing by hand (the act of shaping a round log into a square beam with little more than an axe and the resilience of a native Mainer) is a slow-going and laborious task. But for a maker whose creativity is informed by the ebb and flow of Maine’s seasons and shores, when nature is involved, Stephen knows that rushing simply isn’t an option. Of his process, the woodsman says: “Typically, I search for and select the logs—oftentimes already fallen—and do all my cutting and hewing right there in the forest. After hauling the piece out by hand, it needs to dry for a year or more before I can apply any type of finish.”

The subjects of Stephen’s work vary like the edges in grain. “There’s a soulfulness to each piece that is a direct result of it being shaped by hand,” he says. “I simply take what nature has already so beautifully created and, without unnecessary embellishment, give it new purpose.”

Contemporary Ceramics Rooted in Comfort

Zach Orenstein’s ceramic mugs, cups, vases, and bottles please the eye as well as the hand. Photos by Zach Orenstein and Ronn Orenstein.

Zach Orenstein in his studio.

After a spell working for a large tech company—and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic—Zach decided to forge his own creative path forward, winding his way back to his true calling: ceramics. His line of speckled—and rarer, marbled—mugs, vases, and bowls is a colorful and abstract contrast to the more common kitchenware varieties. Inspired by texture and color, Zach makes a calculated concoction of mason stain, water, and porcelain. After that, each piece is hand-shaped, fired, sanded (twice at different stages in the process to smooth out any and all imperfections), and glazed. This potter’s mesmerizing and sought-after marbled pieces require working with different types of clay, oftentimes having varying levels of firmness. Rainbow marbled pieces use more material and require a meticulousness that Zach admittedly relishes. “The key in this type of work is to not be afraid to fail,” Zach divulges. “My first pottery teacher taught me that in high school, and I’ve been experimenting and enjoying ever since.”

Rugged Wares for the Stylish Minimalist

Amie Kennedy proudly utilizes salvaged textiles in her custom goods.

Durability, function, and purpose inspire Kennedy & Co. product designs.

Amie’s creative process is informed by her military service, which taught her resourcefulness and refinement.

Amie Kennedy, proprietor of Kennedy & Co.

Using the highest quality ingredients—responsibly sourced beeswax, almond oil, and cocoa butter, for example—Amie also makes and sells her own unique blend of leather balm to uphold the lasting quality of her products.

Enrolling in the Maine College of Art textiles and fashion program after the military propelled her toward a course in shoemaking. There, she discovered the lure—and subsequent love—of leather. Amie began to use the “rugged and simple beauty” of Maine to inform her one-of-a-kind designs. “Maine is a part of me and therefore a part of what I make. It has an inexplicable quality that humbly captivates—something I hope to reflect in my creations,” she says.

Feel near the sea even from afar with a tote from Wildwood Oyster Co.

Becky McKinnell models a dock-line heart-knot rope necklace.

Becky McKinnell, proprietor of Wildwood Oyster Co.

Sea-Inspired, Maine-Made

From her home studio in Cumberland, Becky McKinnell makes original leather, dock-line, and wax canvas goods, including bags, totes, clutches, necklaces, and more. Serendipity and a unique birthday gift helped get her creative endeavor under way. “I’ve always been crafty,” says Becky, reminiscing about her time as an art major at the University of Southern Maine. Upon graduation, her career turned toward the digital realm, but she missed time spent working by hand. When she and a group of close friends started hosting a craft night, Becky experimented with leather by creating a wallet. Soon after, her sister gifted her a leather hide, and Becky set to work creating a bag. “I just made it for me, but suddenly as I wore it around, I began receiving compliments from people wondering where they could get one,” Becky says.

In 2018, she opened shop under the name Wildwood Oyster Co., a name that was originally dedicated to a blog about her and her husband’s residential oyster farm. Working in partnership with other local businesses—such as Maine-Line Industries, Hamilton Marine, and Zootility—Becky seeks to “bottle up the feeling of being near, by, or on the sea” within her minimalistic and rugged pieces. “I’m so humbled by the response I’ve received,” Becky says. “Maine is so special to so many individuals, and to be able to create something that people can remember a place by is incredibly rewarding.”

From Blade to Blade

Packaged in a handmade walnut-and-bamboo box, these trusty tools arrive user-ready. Photos by Chris Blackburn and Jackson Blackburn.

The blade finish is called forced “pattern” patina, which helps preserve the knives.

Each blade is made from a repurposed antique saw.

Hannah and Chris Blackburn, proprietors of Full Circle CraftWorks.

Chris and Hannah met at the Rhode Island School of Design and began their life together in Providence before winding their way back to Maine. Now, from the barn on their property—which was converted into a wood- and metal-working studio well before the animals came along—Chris makes knives from antique, handheld saw blades dating back to the 19th and early 20th centuries. Once used to fell the region’s enormous trees, the two-person saw blades don’t see much work in the power-tool age, though, as Chris puts it, he’s found a way to give them a new life. With his signature forced-patina finish—a technique that protects the high-carbon-steel knives from rust—and hand shaped wooden handles, Chris’s knives are made to cut and carve in style upon arrival, packaged in a handmade walnut-and-bamboo box. In addition to their knives, Hannah and Chris make beeswax candles, candleholders, and gold-gilded pinecones and acorns. While making tools for their homesteading activities is always on their minds, their knives are artful and trusty, a staple for the kitchen, the barn, and the display case.

These items are brought to life with playful patterns and organic edges.

This cup, bowl, and board began as rough burl or “blanks”; Peggy’s artful hand turned them into masterpieces.

Peggy Farrington, proprietor of PF Woodturning.

Spinning Beauty from Burl

Native Mainer Peggy Farrington began woodturning two years ago after happening upon a Facebook video. “I probably watched that video 100 times,” Peggy says. “I was immediately mesmerized.”

Inspired to create to relieve the stress of a full-time job in health care, Peggy took a woodturning class in South Portland, purchased the necessary equipment, and set up a studio in her Scarborough home, selling her creations under the name of PF Woodturning. Likening the act of woodturning to spinning pottery, Peggy creates both decorative and utilitarian bowls, vases, plates, platters, and more. Of her work, Peggy says, “I love how you essentially begin with a chunk of wood—a piece that perhaps came from a fallen tree or the firebox—and through the turning process, uncover something beautiful.” For example, one of her favorite creations, Imperfection, began as a piece of burl wood—rough, yet full of character—and transformed into a gorgeous raw bowl through a 12-hour process. Working with “blanks” of maple and other native species, Peggy uses a chain saw, lathe, chisel, and gouge to shape and mold each creation to her liking. Ever inspired by the characteristics—and characters—of Maine, Peggy creates wares that need not be embellished, representative of the understated workmanship that echoes throughout the region, earnestly reflected in her work.

Glasswares for the Artful Traditionalist

This eye-catching collection of colored glassware by Joseph Webster is made for everyday use. Photos courtesy of Joseph Webster Glass.

A refined stemware collection crafted for the display case and special events.

Joseph Webster in his studio.

A Maine native, Joseph was always keen on pursuing the arts, gravitating toward 3-D media such as pottery and jewelry. While taking a course in ceramics at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts on Deer Isle, Joseph witnessed a glassmaking class and became entranced, hungry to learn and master. Today, with local representation by Maine Craft Portland and Maine Art Hill, not only has Joseph made glass with a striking dedication to honor tradition, but he’s also made a name within his medium and within the state.