As far as impulse buys go, it was a doozy. The first time Dianne Haas, a Boston-based architectural designer, saw the Bridge House, it was a mess. Falling down, just like the song goes about that bridge in London.

On her way to Vinalhaven with time to spare, she’d driven past it by chance. “I had a guidebook with me, it said ‘South Bristol: Authentic Fishing Village,’” said Dianne. “I went across the bridge and here is this building, falling apart, with a cardboard sign that said, ‘For Sale.’ A cardboard sign!” Curiosity piqued, she called the number, left a message, and went ahead with her trip. But the building bewitched her. On her way back, she called again. This time, the owner answered and met her there. Dianne made an offer on the spot.

“It was just a spur-of-the-moment, impulsive decision. I had no intention at all of buying anything in Maine,” she says with a helpless laugh. “But I couldn’t resist.”

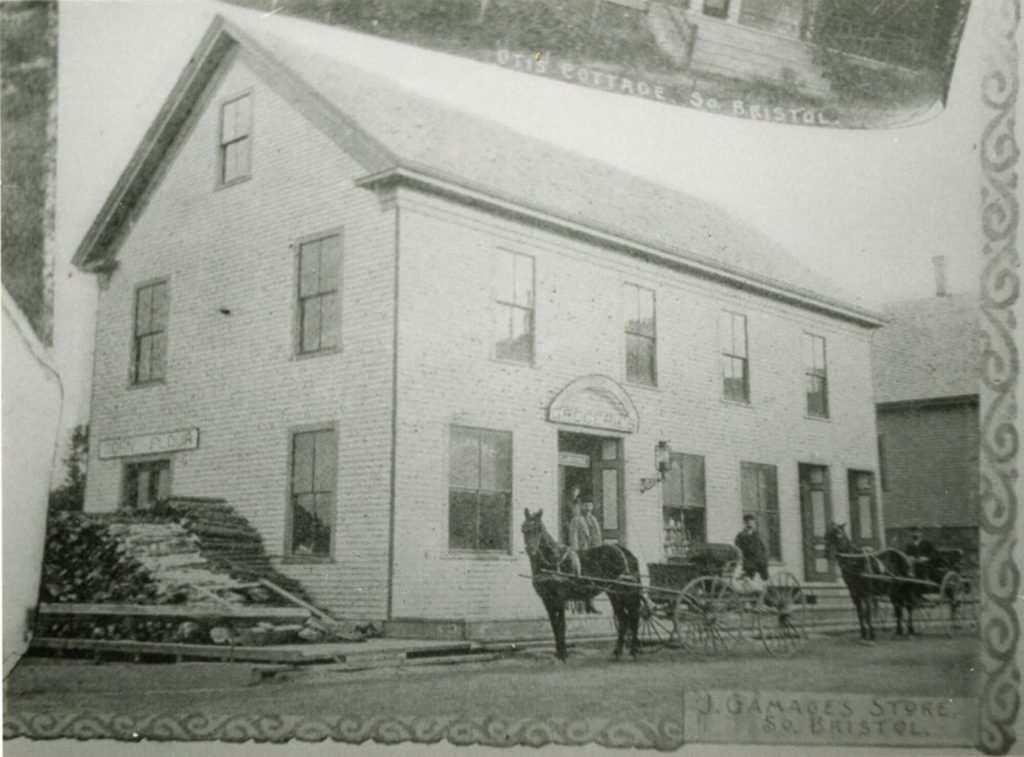

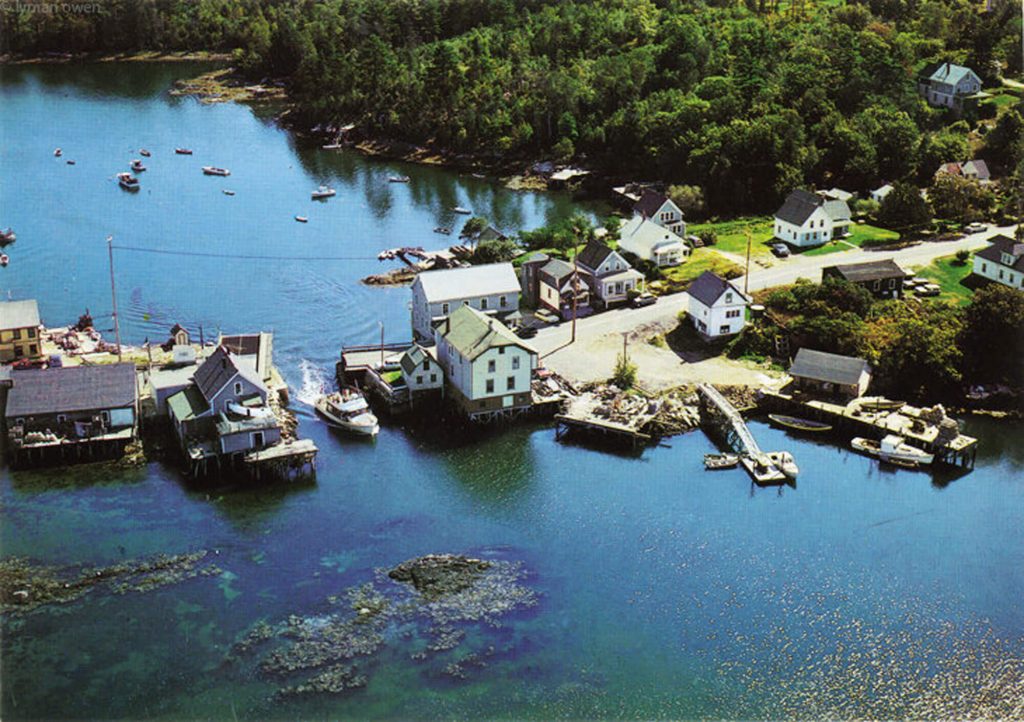

Located on Rutherford Island, the 3,600-square-foot building perches on pilings just across a narrow tributary (known locally as “The Gut”) from South Bristol. Erected in 1894 by Everett Gamage, in the ensuing decades it served as a little bit of everything: grocery store, post office, dance hall, movie theatre, and bowling alley.

“Evidently it had been for sale for years,” Dianne continues. “Nobody wanted it. They didn’t think it could be restored.” Now, thanks to the mother-son duo behind Taylor Haas Studio, the building is restored to its former utility and beyond.

As architects and designers, Dianne and her son, Christopher Taylor (of CjT Architects in Boston), were up for the challenge. But with it came fresh hurdles. “There were a lot of things I didn’t know,” she admits. “I’d never bought a building that sat on pilings in the water. I knew nothing about that engineering. It had to be lifted off the foundation by a building mover on a barge, and all the pilings underneath had to be replaced while the building was up in the air.”

The duo teamed with local contractor Kenneth Lincoln to complete the tricky job over the course of three years. “The building didn’t have any plumbing, water supply, or septic system,” Chris adds. “We needed to add two kitchens, three full baths, and one half-bath. We wanted to do this in a way that involved building as few new walls as possible and keeping all historical aspects of the building intact. We also wanted to make sure that the cistern, water purification system, and holding tank for wastewater would be safe, sustainable, and last for a long time.”

The process was painstaking—and worth it. The warm patina of the interior’s wood-clad envelope was mostly preserved, the period windows were restored. “Every board is original. If we had to take it off to do anything underneath, they were marked and put back,” Dianne notes with pride.

In keeping with the commercial zoning, Dianne initially opened the Bridge House Café (now closed) on the ground floor and rented space to a kayak outfitter. Clad in gray clapboard, the building’s boxy exterior looks much as it always has, but the charm-filled interior tells another story. Several of them, in fact.

The second floor, which once served as the community’s dance hall and movie house, was transformed into a multi-use space for living, cooking, and dining. In the corner, you can still spy the spot where the movie projector once perched. While under restoration, the building divulged more secrets. Dianne suspects that during the site’s dance hall days, a third-floor supply room may have once been a love nest. The names of lovebirds who carved their devotion into the walls (Say, “‘Bill + Joan,’” she offers.) were preserved and can be spied in a third-floor bedroom. “I don’t think anybody knew that they were going up there,” says Dianne.

Major effort ensured that the building’s authenticity was maintained. “The bookshelves are reclaimed from the original benches that lined the sides of the dancehall,” Chris points out. “All materials and fixtures inside the building are either original, reclaimed, or antiques that are historically accurate for a late-1800s building.” A favorite detail? “There’s also a small, original ticket window in the staircase leading up to the second floor, which I love!”

Other clues of the building’s past vocations dovetail as decor. A vintage post-office sign, an old piano, bowling pins salvaged from the torn-down alley, are tokens from another time. But the best part of all may be the ageless waters that surround it, the Johns River on one side, the Damariscotta River on the other. “No matter where you look you just see water,” relishes Dianne.

The building now contains Dianne’s three-season home and office, Bridge House Design. Out back, where the bowling alley once stood, is an expansive deck and deep-water dock where you can idle all afternoon watching the progress of lobster boats and the raising and lowering of the drawbridge that gives the house its name. As it has done for generations, the Bridge House stands sentinel above the lively waterway, so close to the toll booth that Dianne can keep up a running conversation with the bridge keepers from her deck.

“I didn’t know how long it would take me to do it,” she reflects. “I just knew that it was a fabulous building in a great location, in a great town, and it would be a shame to have it just fall in the water. That would’ve been the end of it.” What for some might have been a folly has been transformed, with time and expertise, into the ultimate island retreat. “I was determined to do it,” Dianne concludes, with clear satisfaction. “A lot of people thought it could never happen, and I was determined that it was going to happen.”