Alex Katz is a master of contradictions. Over a career that spans nearly eight decades, the artist continually balances the simple and complex, the personal and impersonal, the familiar yet unknowable. Yet another dichotomy: as a New York City native, Katz’s relationship with Maine runs deep. Scholarships to study at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in the summers of 1949-50 led to the eventual purchase of a home beside Coleman Pond in Lincolnville, where he has summered and worked in the adjacent studio for nearly 70 years. This urban-rural polarity affords a certain tension to his oeuvre: the push-pull of scenic vs. scene, capturing both city and country in a way that feels timeless and very much of its time. The ballast of small-town life seems to agree with Katz. Despite a heady life among art world giants and the literati, a Mainer-like matter-of-factness clings to his mien, as indelible as his Queen’s accent.

His relationships with local museums are a gift to the state. Particularly Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, where he has been awarded an honorary doctorate, served on the Board of Governors, and whose Paul J. Schupf wing contains a rotating selection of nearly 900 pieces of his work.

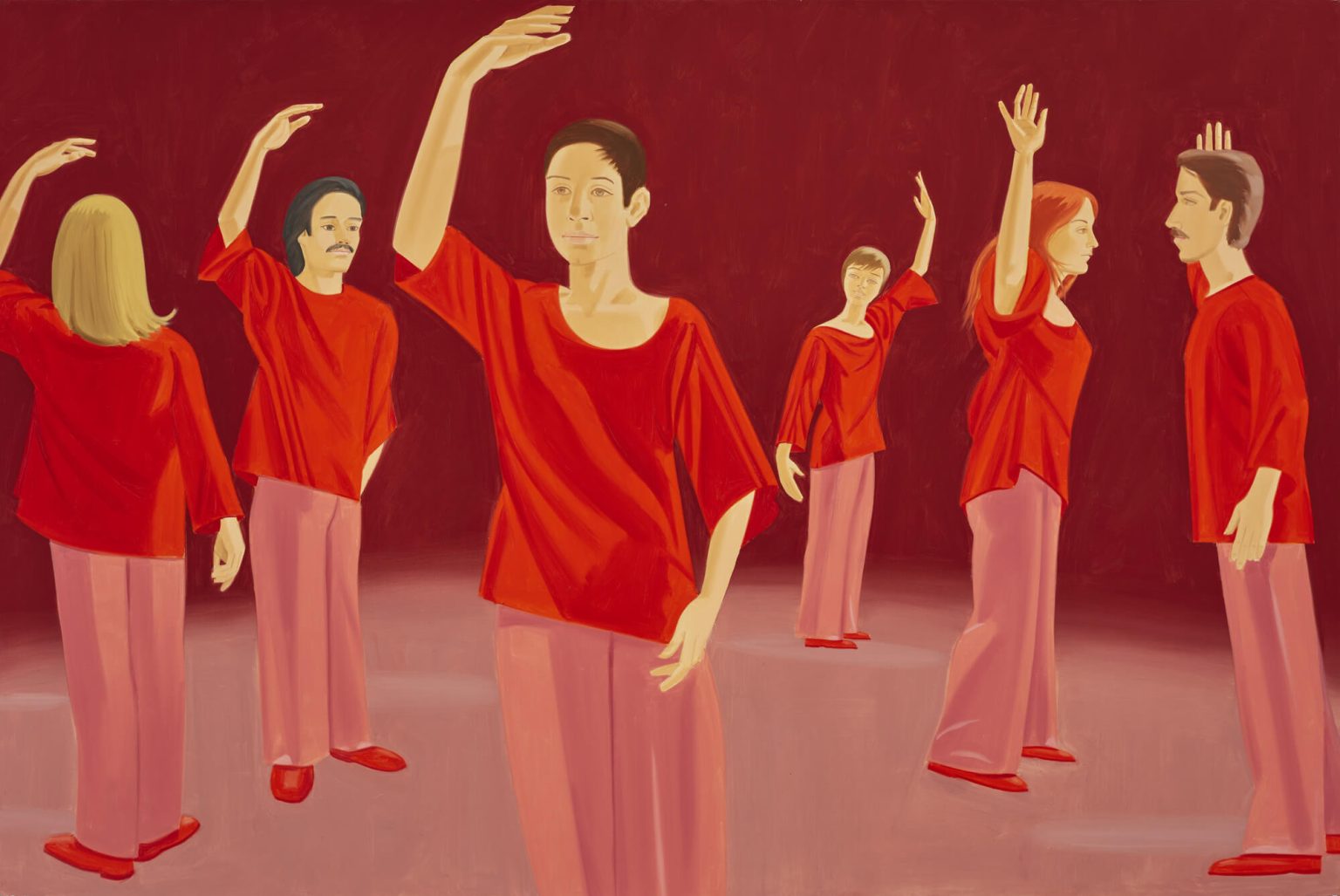

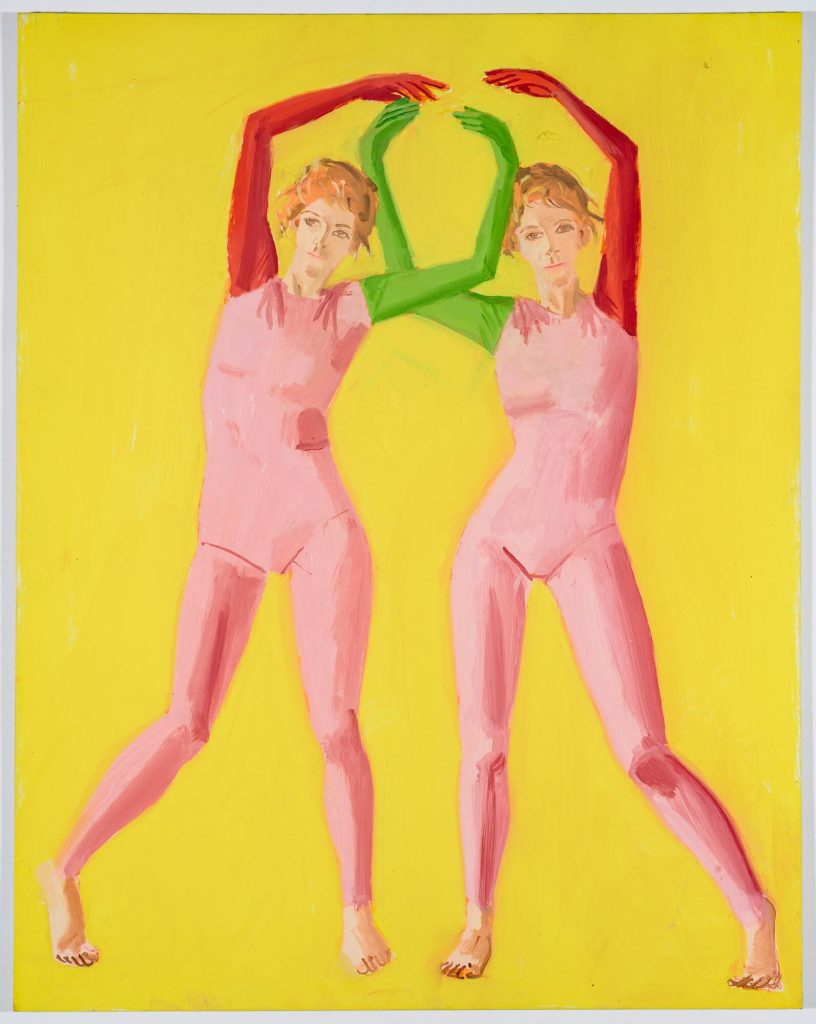

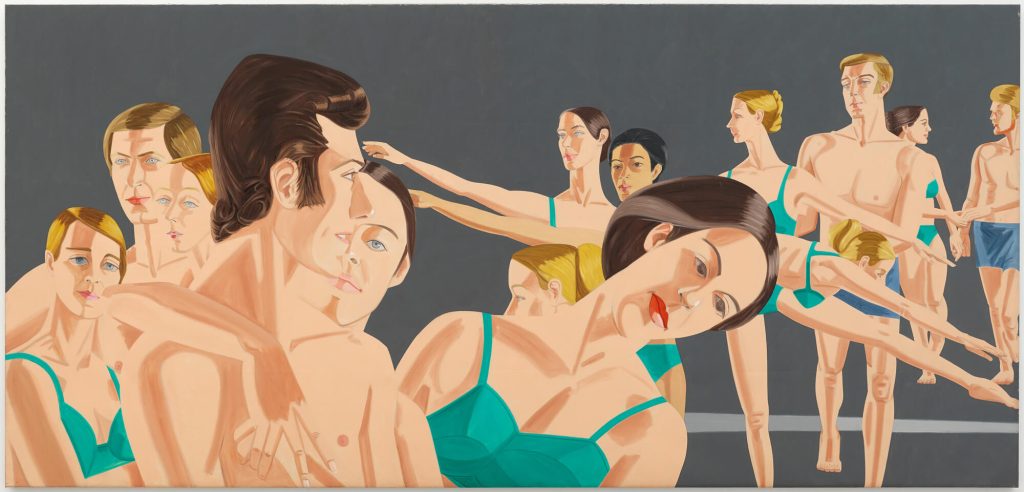

Born in 1927, Katz began painting in his late teens and went on to study under Morris Kantor at The Cooper Union School of Art. During the 1950s and ’60s, a period that would later be defined by abstraction and Pop Art, he remained a stubbornly figurative artist, pledging his allegiance to neither. Like Picasso or Matisse, the modern masters he admires, Katz’s flat, graphic depictions of landscapes and people feel as current as a billboard and as timeless as a Minoan fresco. This single-perspective effect makes the work deceptively elemental, providing instant access to glittering parties and sun-bleached seasides. His most iconic subjects appear to exist without context or shadows, supremely two-dimensional. Many radiate within color block fields, vividly alive inside a precise moment, in what feels like the blink of an eye. Ada, his wife of 65 years, is a perpetual muse, but so too are family friends, poets, writers, and kinetically gifted dancers. Routinely grounded on outsized canvases, his subjects are larger than life, a dominating scale that elevates the mundane to mythos: a coterie of partygoers, dancers, beach bathers, mere mortals—now Valkyries, giants, and gods.

Katz is also known for his cutouts, figures extracted from canvases, painted fore and aft, and mounted on plywood or aluminum to create 4-D sculptures, their profiles as precise as cameos carved in abalone.

The 2022-23 season has been a veritable jubilee for the nonagenarian artist. The Guggenheim dedicated the whole of its vaulted nautilus to Alex Katz: Gathering, a retrospective of his work. Colby College Museum of Art mounted Alex Katz: Theater & Dance, an exhibition that featured Katz’s longtime collaboration with dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor and company, and the celebration continues with Alex Katz: Repetitions, which opened in March and runs through March 2026. Per the Colby website, Katz “transforms the people and places that comprise his two homes—New York City and Lincolnville, Maine—into powerful images that reflect his enchantment with modern life and his dedication to painting. He makes landscapes representing his everyday surroundings, portraits of close friends and family, and genre scenes featuring members of his creative circles.” Additionally, this summer, Alex Katz, Wedding Dress, opened at the Portland Museum of Art (June 30, 2023-June 2, 2024), and showcases a series of his large-scale paintings exploring the intersection of art and fashion.

If Katz’s work feels simple, it is radically, dramatically so—as inscrutable as it is accessible. With his representational style, he welcomes us in, one near-imperceptible brushstroke at a time. He is not offering a rubric any more than he is asking a riddle; he is simply offering his world. What we do once we get there is up to us.