This past March, Lynne Drexler’s Flowered Hundred went up for auction at Christie’s. The famed auction house estimated the painting would garner around $60K on the top end. The final bid landed at $1.2 million. “There is a frenzy right now to acquire her [Drexler’s] work,” says Elizabeth Moss of Moss Galleries in Falmouth and Portland. “In the last two years, the world has woken up to the reality of this woman’s remarkable career.”

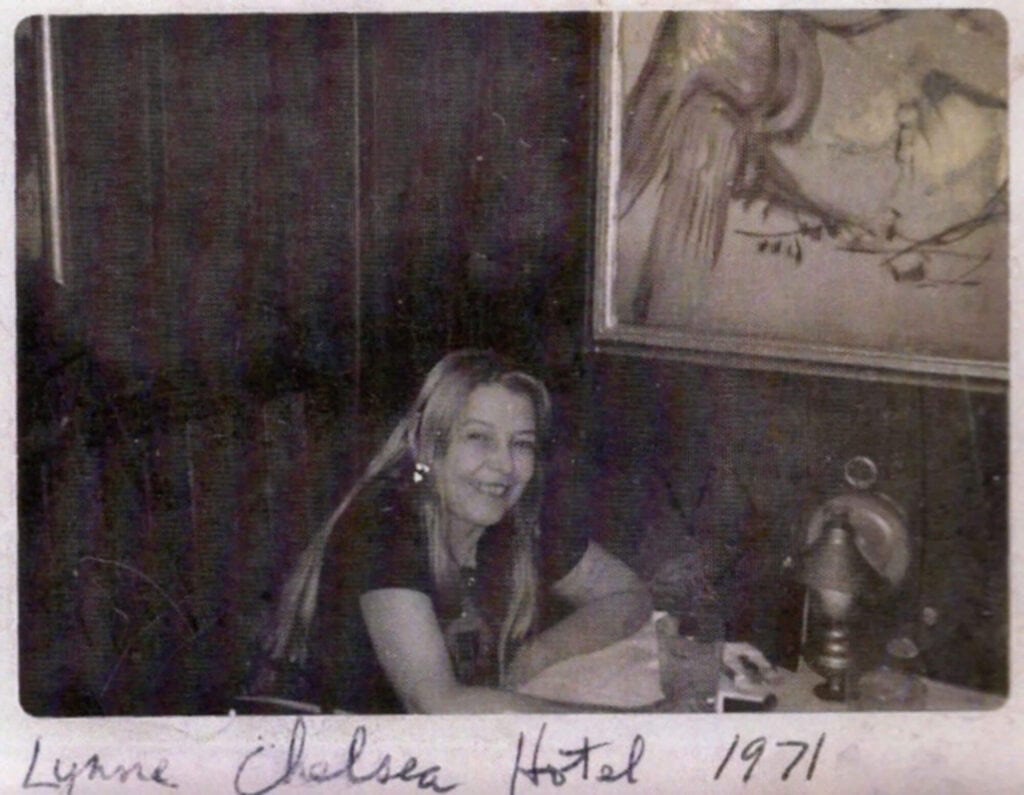

It is heartening to see Drexler finally getting her due in the wider art world, albeit, unfortunately, long after her passing in 1999 on Monhegan Island. Drexler’s background aligned with those of many of her male contemporaries in her lifetime—she studied with Hans Hofmann, New York’s premier teacher of modernism; hung around the Cedar Street Tavern with Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, and other giants of the abstract expressionism movement; lived in the Chelsea Hotel during its bohemian heyday (the owner famously accepted art for rent, and one of Drexler’s pieces hung in the lobby)—but she never received the same level of attention or acclaim. “Here is an artist who stood toe-to-toe with the boys in every way,” says Elizabeth, “but because she was female, I firmly believe she was excluded from the gallery representation that the male abstract expressionists of the time had available to them.”

Still, one gets the sense Drexler would not feel embittered by her posthumous success, would not feel cheated. Her focus was never on fame or fortune, but always, foremost, on her work. Having grown weary of the city, Drexler began summering on Monhegan in 1963 and moved to the island full time in 1983, hoping to continue her work free of the distractions and injustices of the New York art ecosystem. In a letter, Drexler advised one friend how to inform New York collectors of her absence: “I suggested she advise them I’d become a hermit—an eccentric one—and that I only come to NYC when provided with orchestra tickets to the MET, clubhouse tickets to the racetrack and absolutely no talk of art or the scene.”

Indeed, having left the city behind, Drexler, though always industrious, began a period of great output on Monhegan, filling her cottage with paintings, “artwork stacked to the rafters, under her bed and against the bathroom walls,” as Ann Hughey and Helen Feibusch describe it in their essay “On Island,” included in catalog materials for a 2008 Drexler retrospective at the Portland Museum of Art (PMA).

Examining Drexler’s output from this period, one sees her work growing more enmeshed with the island’s natural environment. Drexler’s earliest and perhaps most influential teacher, Hans Hofmann, “believed that the origins of art, even abstract painting, derived from nature,” writes Susan Danly, curator of the PMA show. Drexler’s work on Monhegan shows the artist taking this dictum to heart. “Her paintings from this period appear to be abstractions,” Susan says, “but as her sketchbooks and a cache of small black-and-white snapshots show, Drexler’s images were frequently based in nature or in the architecture that surrounded her, especially on Monhegan Island.” In paintings from this time, one sees felled trees, leafless branches, ragged coastlines, and laundry snapping in breezes off the Atlantic, all incorporated into Drexler’s unique abstract vision.

“When I held her exhibition last December,” Elizabeth says, “I had to repeatedly explain that these paintings are from the ’60s and ’70s because people were shocked that they weren’t contemporary. The pieces look so current. They look brand-new, and in a way, they are brand-new, because no one has seen them for 40 years. Thankfully, that’s changing fast.